Martindale, an associate professor at the Jackson School of Geosciences, recognized the texture from Early Triassic microbial mat examples she had studied in graduate school. Those earlier examples came from shallow, stressful environments or post-extinction settings where photosynthetic microbes could thrive and grazers were scarce. In contrast, the Moroccan wrinkle structures occur in sediments that were originally deposited in the deep ocean, about 600 feet below the surface, a setting long thought to be inhospitable to such microbial mats.

Conventional wisdom held that wrinkle-like features in deepwater rocks formed when turbidity currents or submarine landslides reshaped soft sediment into ridges and furrows. In that view, the structures were purely physical, with no biological component. Martindale was unconvinced, noting that the wrinkled textures overprinted larger ripples produced by the turbidity currents, and closely resembled known microbial mat fossils rather than random deformation structures.

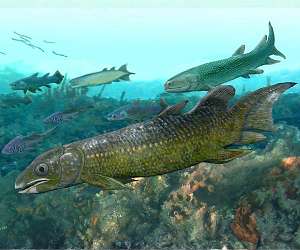

In a new study published in the journal Geology, Martindale and colleagues propose that these wrinkle structures record chemosynthetic microbial mats that colonized the seafloor after a sediment gravity flow. Instead of harvesting sunlight, these microbes used chemical energy from nutrients and reduced compounds transported downslope by the landslide into the deep basin. This chemosynthetic metabolism would have allowed the microbial community to flourish far below the photic zone.

The team suggests that these deep-sea microbial mats may also have produced toxic sulfur compounds, helping to deter grazing by larger organisms and preserving the mat fabric long enough to be buried and fossilized. The resulting wrinkle structures form a subtle, fine-scale overprint on top of the larger ripples made by the turbidity current, creating a composite sedimentary texture. This combination of physical and biological features helped the researchers distinguish microbial mats from purely physical wrinkle-like structures.

Modern analogs for these ancient communities exist on the deep ocean floor today. Microbial mats colonize nutrient-rich patches such as whale falls, where carcasses that sink to the seafloor support dense, dark-ocean ecosystems. Similar chemosynthetic microbes, known as chemolithotrophs, tap chemical gradients rather than sunlight for energy in these settings. The new work argues that comparable communities may have been forming wrinkle structures in deepwater turbidites during the Early Jurassic.

Jake Bailey, a University of Minnesota scientist who studies microbe-environment interactions and was not involved in the research, notes that the findings expand how geologists interpret wrinkle structures in the rock record. Many paleontologists and sedimentologists have traditionally associated such textures with phototrophic microbial mats in shallow water. The new interpretation shows that some ancient wrinkles may instead record chemolithotrophic communities in the dark ocean, broadening the range of environments where microbial mat fossils may be preserved.

Martindale emphasizes that the discovery highlights a potential bias in how geologists classify wrinkled sedimentary surfaces. If all such structures in deepwater deposits are assumed to be purely physical, biologically generated textures could be overlooked or misidentified. The problem is compounded by loose terminology: the simple label "wrinkly" covers a wide variety of features, from soft-sediment deformation to true microbial mat fabrics, without a precise diagnostic vocabulary.

The work also marks a departure from Martindale's usual focus on ancient coral reefs and mass extinctions. The detour into deep-sea microbial mats began with a single puzzling outcrop and a geologist trained to recognize the right textural "search image." Martindale describes the project as an unexpected path driven by curiosity and persistence, sparked by the realization that the Moroccan wrinkles did not fit the standard deepwater explanation.

According to the researchers, recognizing chemosynthetic microbial wrinkle structures in turbidites could significantly increase the known occurrences of such communities in the fossil record. That, in turn, would reshape views of how microbial ecosystems occupied the deep ocean through time, and how often they were preserved in sediments traditionally interpreted as purely physical deposits. The study underscores how small textural details in ancient rocks can reveal hidden ecosystems and challenge long-standing assumptions about where life flourished on the early Earth.

Research Report: Chemosynthetic microbial communities formed wrinkle structures in ancient turbidites

Related Links

University of Texas at Austin Jackson School of Geosciences

Explore The Early Earth at TerraDaily.com

| Subscribe Free To Our Daily Newsletters |

| Subscribe Free To Our Daily Newsletters |