A new study led by researchers at the University of Wisconsin Madison used Escherichia coli and its bacteriophage predator T7 to probe how microgravity reshapes the coevolution between phages and bacteria during spaceflight.

The work, published in PLOS Biology, shows that the phage can successfully infect E. coli in orbit, but the timing and outcome of infections differ from those seen in ground based controls.

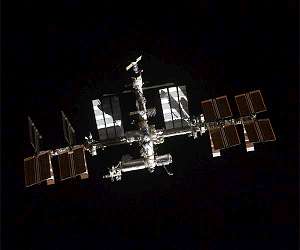

The team prepared parallel sets of E. coli cultures infected with T7, incubating one set on Earth and sending the other to the International Space Station to experience microgravity conditions.

Analysis of the ISS samples showed that T7 infection proceeded only after an initial delay, indicating that spaceflight slows early stages of virus host encounters without completely blocking infection.

Whole genome sequencing then revealed that both the phages and the bacteria accumulated distinctive patterns of mutations in space compared to their counterparts on Earth.

Phages evolved specific changes that appear to improve their ability to bind to and infect bacterial cells, including mutations in proteins that recognize receptors on the E. coli surface.

At the same time, the space flown E. coli populations acquired mutations that may strengthen defenses against phage attack and enhance their chances of surviving in near weightless conditions.

To dissect how these changes affected a key viral component, the researchers applied deep mutational scanning to the T7 receptor binding protein, which is central to recognizing and attaching to host cells.

This high throughput approach systematically evaluated how thousands of possible amino acid substitutions influenced receptor binding, revealing that microgravity favored a different set of beneficial variants than those selected on Earth.

Follow up experiments conducted under normal gravity linked microgravity associated receptor binding variants to increased activity against disease causing E. coli strains that normally resist T7 and are implicated in urinary tract infections.

These findings suggest that microgravity conditions can steer phage evolution toward functions that have practical value back on Earth, including the development of candidate therapeutics against drug resistant bacterial pathogens.

The study underscores that spaceflight changes not only the physiology of microbes but also the physical environment in which viruses and bacteria encounter each other, altering the rules of their evolutionary arms race.

According to the authors, space fundamentally shifts how phages and bacteria interact, slowing infection and pushing both organisms along evolutionary paths that diverge from those on Earth, yet those same adaptations can be harnessed to engineer improved phages for use in human health applications.

The work highlights the International Space Station as a unique platform for exploring microbial adaptation and for uncovering new strategies to combat antibiotic resistant infections using tailored bacteriophages.

Research Report:Microgravity reshapes bacteriophage host coevolution aboard the International Space Station

Related Links

University of Wisconsin-Madison

Space Medicine Technology and Systems

| Subscribe Free To Our Daily Newsletters |

| Subscribe Free To Our Daily Newsletters |