The scientists found that the wobble could grow in a new, unexpected way. Researchers already knew that wobbles could grow from the interaction between plasma and magnetic fields in a gravitational field. But these new results show that wobbles can more easily arise in a region between two jets of fluid with different velocities, an area known as a free shear layer.

"This finding shows that the wobble might occur more often throughout the universe than we expected, potentially being responsible for the formation of more solar systems than once thought," said Yin Wang, a staff research physicist at the U.S. Department of Energy's (DOE) Princeton Plasma Physics Laboratory (PPPL) and lead author of the paper reporting the results in Physical Review Letters. "It's an important insight into the formation of planets throughout the cosmos."

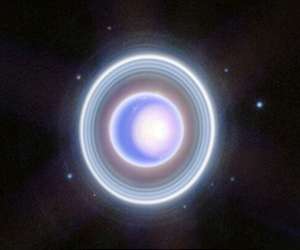

The findings follow up on previous results from 2022 that focused on a simpler picture of fluid behavior. Together, the two findings strengthen the evidence that a type of plasma wobble known as the magnetorotational instability (MRI) can cause the formation of planets from so-called accretion disks of matter circling stars.

Using computer programs to analyze the 2022 results, the scientists confirmed that they had created a form of the MRI in which magnetic field lines do not have the same orientation around and through the plasma. Instead, they wound around in a twisting shape, interlacing through the free shear layer and developing different strengths in different orientations.

Just as in the 2022 result, the wobble causes particles on the outside of the plasma to move more quickly and those on the inside to move more slowly. While the quick particles can gain so much speed that they fly off into space, the slow particles can fall inward and coalesce into bodies, including planets.

The new simulations showed the researchers that this uneven wobble, or nonaxisymmetric MRI, is a type of magnetohydrodynamic instability. It resembles turbulence caused by the meeting of fluids of different velocities - like the swirls caused by an airplane flying through a cloud - but with added complexity caused by a magnetic field. Similar turbulence occurs on the sun's surface and in the region of space influenced by Earth's magnetic field.

Collaborators included Erik Gilson, head of PPPL's discovery plasma science; Hantao Ji, a PPPL distinguished research fellow and professor of astrophysical sciences at Princeton University; Jeremy Goodman, a professor of astrophysical sciences at Princeton University; and Hongke Lu, a summer intern.

This research was supported by DOE under contract number DE-AC02-09CH11466, NASA under grant number NNH15AB25I, the National Science Foundation under grant number AST-2108871 and the Max-Planck-Princeton Center for Fusion and Astro Plasma Physics.

Related Links

Princeton Plasma Physics Laboratory (PPPL)

Lands Beyond Beyond - extra solar planets - news and science

Life Beyond Earth

| Subscribe Free To Our Daily Newsletters |

| Subscribe Free To Our Daily Newsletters |