The approach relies on the rare isotope thorium-229, which must be extracted from weapons-grade uranium, leaving an estimated global supply of only about 40 grams for research and potential devices. This scarcity makes it important to reduce the thorium required in each sample while still maintaining the nuclear response needed for clock operation.

In their earlier experiments, the researchers embedded thorium-229 in specially prepared fluoride crystals that stabilized the nuclei and remained transparent to the laser light used to excite the nucleus. The crystal growth process took years to optimize, required at least 1 milligram of thorium per sample, and remained difficult to scale given the limited worldwide inventory.

"We did all the work of making the crystals because we thought the crystal had to be transparent for the laser light to reach the thorium nuclei. The crystals are really challenging to fabricate. It takes forever and the smallest amount of thorium we can use is 1 milligram, which is a lot when there's only 40 or so grams available," said first author and UCLA postdoctoral researcher Ricky Elwell, who received the 2025 Deborah Jin Award for Outstanding Doctoral Thesis Research in Atomic, Molecular, or Optical Physics for last year's breakthrough.

In the new study, Hudson's group instead electroplated a very small amount of thorium onto stainless steel by modifying standard jewelry electroplating methods. Electroplating passes an electric current through a conductive solution to deposit a thin layer of atoms from one metal onto another, allowing thorium to form a surface layer on a robust steel substrate.

"It took us five years to figure out how to grow the fluoride crystals and now we've figured out how to get the same results with one of the oldest industrial techniques and using 1,000 times less thorium. Further, the finished product is essentially a small piece of steel and much tougher than the fragile crystals," said Hudson.

The team realized that a central assumption about the host material was incorrect: the thorium did not need to sit inside a transparent medium for the nuclear transition to be excited and measured. Re-examining this constraint allowed them to design experiments where a laser still drives the nuclear transition even though the supporting material is opaque.

"Everyone had always assumed that in order to excite and then observe the nuclear transition, the thorium needed to be embedded in a material that was transparent to the light used to excite the nucleus. In this work, we showed that is simply not true," said Hudson. "We can still force enough light into these opaque materials to excite nuclei near the surface, and then, instead of emitting photons like they do in transparent material such as the crystals, they emit electrons which can be detected simply by monitoring an electrical current - which is just about the easiest thing you can do in the lab!".

In the electroplated samples, excited thorium nuclei release electrons rather than detectable photons, and the resulting electrical current provides a straightforward signal of the nuclear transition. This readout method, combined with the mechanical strength of steel and the much lower thorium loading, points to a path for compact, durable nuclear-clock components.

Thorium-based nuclear clocks are being studied for roles in communication networks, power grid synchronization, radar systems, and navigation where GPS signals are unavailable or disrupted. Submarines already use atomic clocks for underwater navigation but must periodically surface to correct accumulated timing errors, a limitation that more stable nuclear clocks could reduce.

"The UCLA team's approach could help reduce the cost and complexity of future thorium-based nuclear clocks," said Makan Mohageg, optical clock lead at Boeing Technology Innovation. "Innovations like these may contribute to more compact, high-stability timekeeping, relevant to several aerospace applications.".

Improved nuclear clocks are also seen as important for deep-space missions, where spacecraft must navigate without continuous satellite support. Greater timing stability would support more autonomous navigation and could lower reliance on ground-based tracking as crews travel farther from Earth.

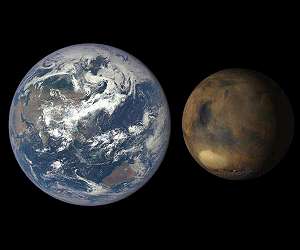

"The UCLA group led by Eric Hudson has done amazing work in teasing out a viable way to probe the nuclear transition in thorium - work extending over more than a decade. This work opens the way to a viable thorium clock," said Eric Burt, who leads the High Performance Atomic Clock project at the NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory and was not involved in the research. "In my opinion, thorium nuclear clocks could also revolutionize fundamental physics measurements that can be performed with clocks, such as tests of Einstein's theory of relativity. Due to their inherent low sensitivity to environmental perturbations, future thorium clocks may also be useful in setting up a solar-system-wide time scale essential for establishing a permanent human presence on other planets.".

The project received support from the National Science Foundation and involved researchers from the University of Manchester, the University of Nevada Reno, Los Alamos National Laboratory, Ziegler Analytics, Johannes Gutenberg-Universitat Mainz, and Ludwig-Maximilians-Universitat Munchen.

Research Report:Laser-based conversion electron Mossbauer spectroscopy of 229ThO2

Related Links

University of California Los Angeles

Understanding Time and Space

| Subscribe Free To Our Daily Newsletters |

| Subscribe Free To Our Daily Newsletters |