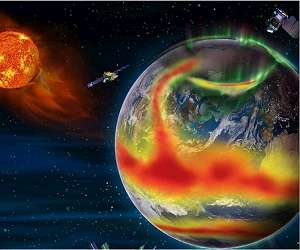

The solar wind, a continuous flow of charged particles from the Sun's atmosphere (corona), extends beyond Earth, interacting with our atmosphere to produce the auroras. The 'fast' solar wind travels at speeds exceeding 500 km/s (1.8 million km/h). Initially, the wind exits the Sun's corona at slower speeds, suggesting an unknown mechanism accelerates it as it travels further from the Sun. While it naturally cools as it expands into space, the cooling rate is slower than anticipated, indicating an additional energy input.

The key question - what provides the energy to accelerate and heat the fastest solar wind - has been answered through data from Solar Orbiter and Parker Solar Probe. These instruments have confirmed that large-scale oscillations in the Sun's magnetic field, known as Alfven waves, are responsible for this energy transfer.

"Before this work, Alfven waves had been suggested as a potential energy source, but we didn't have definitive proof," explained Yeimy Rivera, joint first author from the Center for Astrophysics, Harvard and Smithsonian, Massachusetts.

In contrast to ordinary gases, which only transmit sound waves, the Sun's atmosphere, being a plasma, responds to magnetic fields, allowing the formation of Alfven waves. These waves store and transmit energy efficiently through the plasma. Both Solar Orbiter and Parker Solar Probe have the necessary instruments to measure the properties of this plasma, including its magnetic field.

In February 2022, despite their different orbits, Parker Solar Probe and Solar Orbiter aligned along the same stream of solar wind, allowing for a unique comparative study. Parker, operating at 13.3 solar radii (about 9 million km) from the Sun, sampled the solar wind stream first, followed by Solar Orbiter at 128 solar radii (89 million km) a day or two later. "This work was only possible because of the very special alignment of the two spacecraft that sampled the same solar wind stream at different stages of its journey from the Sun," added Yeimy.

By comparing the measurements from both spacecraft, the team observed that a significant portion of the magnetic energy detected by Parker Solar Probe had been converted into kinetic and thermal energy by the time it reached Solar Orbiter. This conversion process was crucial for the acceleration and heating of the solar wind.

The research also highlighted the role of magnetic configurations known as switchbacks - large deflections in the Sun's magnetic field lines, which are a form of Alfven waves. These switchbacks, first observed in the 1970s and more recently by the Parker Solar Probe, are now understood to play a critical role in the acceleration and heating of the solar wind.

"This new work expertly brings together some large pieces of the solar puzzle. More and more, the combination of data collected by Solar Orbiter, Parker Solar Probe, and other missions is showing us that different solar phenomena actually work together to build this extraordinary magnetic environment," said Daniel Muller, ESA Project Scientist for Solar Orbiter.

Moreover, the findings have implications beyond our Solar System. "Our Sun is the only star in the Universe where we can directly measure its wind. So what we learned about our Sun potentially applies at least to other Sun-type stars, and perhaps other types of stars that have winds," Samuel Badman, joint first author, explained.

The team is now extending their analysis to investigate whether the Sun's magnetic field energy influences the acceleration and heating of slower solar wind streams.

Research Report:'In situ observations of large amplitude Alfven waves heating and accelerating the solar wind'

Related Links

Solar Orbiter

Solar Science News at SpaceDaily

| Subscribe Free To Our Daily Newsletters |

| Subscribe Free To Our Daily Newsletters |